Abstract: The whole world suffered the consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic. The daily life of people and their habits were changed abruptly by the (mobility restricting) sanitary measures put in place in different countries. Before the COVID-19 pandemic, work and leisure defined the different days of the week, creating a certain pattern, which, as we’ll find out, had a periodicity of a week. Now, the interesting thing is to ask whether the COVID-19 pandemic made us lose sense of this typical week. In other words, what we want to see is: if there was a pattern initially, how did it change during Covid? Wikipedia is known to be a relatively good measure of people’s search queries and computers and phones are increasingly defining people’s lives. Wikipedia viewership thus has the potential to enlighten us on the changing habits of people as mobility restrictions due to covid happened. We all have a feeling that our routines changed but can we prove it? And can we quantify it?

1. Goal of the study

Our study addresses the following two questions:

- Are there Wikipedia viewing habits (patterns) during a normal year (year without Covid)?

- Considering viewing habits vary from work week to weekends, did this pattern change during Covid? And if so, how?

1.1 Data discovery

We will work with one principal dataset that comes from the 2020 paper Sudden Attention Shifts on Wikipedia During the COVID-19 Crisis by Manoel Horta Ribeiro, Kristina Gligoric, Maxime Peyrard, Florian Lemmerich, Markus Strohmaier, and Robert West [1]. It contains aggregated time-series of Wikipedia pageviews for 12 languages editions with pageviews on both desktop and mobile devices.

Among the 12 languages, we decided to study 9 of them, that can be found in the following table containing the mobility change point date, the return to normalcy date for each language and if the country to which the language can be tied to underwent a lockdown. Here, the mobility change point and normalcy dates are found in Horta Ribeiro et al (2020) [1], and correspond to sharp changes in mobility timeseries provided by Google that allow us to detect when the population began to spend considerable more time at home than usual and when people went back to their normal daily lives.

| Country | Danemark da |

Finland fi |

Italy it |

Japan ja |

Netherlands nl |

Norway no |

Serbia sr |

South Korea ko |

Sweden sv |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mobility Change Point | 2020-03-11 | 2020-03-16 | 2020-03-11 | 2020-03-31 | 2020-03-16 | 2020-03-11 | 2020-03-16 | 2020-02-25 | 2020-03-11 |

| Normalcy Change Point | 2020-06-05 | 2020-05-21 | 2020-06-26 | 2020-06-14 | 2020-05-29 | 2020-06-04 | 2020-05-02 | 2020-04-15 | 2020-06-05 |

| Lockdown | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No |

Note: In our case, “change due to Covid-19” is actually a “change due to the change in mobility caused by COVID-19”. The beginning of the COVID-19 period and the beginning of mobility restrictions will be considered to be on the same date for each country in this study.

Note 2: This study focuses on languages that can be easily tied to one country. These assumptions are based on the study Just how many people are reading Wikipedia in your country, and what language are they using? [2]. Furthermore, we make the assumption that Wikipedia readers are representative of the country population. For example, we assume that readers of the Swedish edition of Wikipedia are representative of all the citizens of Sweden. Based on this, we will consider the two terms ‘country’ and ‘language edition’ to have the same meaning. Therefore, they will be used interchangeably.

The pageviews are distributed among 64 topics which can be grouped into 4 categories:

- Geography,

- History and Society,

- Culture and

- STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, Maths).

So, what do we read most on Wikipedia? The plot above shows the distribution of all the pageviews between the 4 main categories for the 9 language editions considered. The time frame studied ranges from the mobility changepoint to the return to normalcy in both 2019 and 2020 specific to each language. From this, we make the following observations:

- The most read categories stayed the same during COVID-19: Culture and Geography .

- There are very few outliers in 2019, meaning the distribution of views between the different categories stayed pretty much the same all throughout the studied period.

- On the other hand, there are a lot more outliers in 2020, suggesting there was more volatility regarding the topics that were most viewed.

Moreover, we can dive deeper and we plot below the topics that were the most read in each country:

Surprisingly, we see that:

- The battle for 1st place in the heart of Wikipedia readers is between the geographic region where they live (a Japanese will tend to read a lot of Wikipedia pages about Asia or East Asia while an Italian will read pages about Europe) and STEM (often used for school, at university, …).

- Following closely, come the Media topic and the Biography topic, both belonging to the Culture category.

Now that we know what we’re talking about, can we get into the swing of things?

2. Does the week make sense pre-covid?

The goal of this part is to find out if people had habits in the way they consulted Wikipedia before COVID-19 impacted their mobility, and what those habits were.

2.1. What’s the periodicity of Wikipedia pageviews?

Our intuition was that we could find a weekly pattern in Wikipedia pageviews (spoiler, we did!), as we think it is not consulted in the same way on working days and on days off. On the graphs below, the number of pageviews for each category and for each country are displayed from January, 1st of 2019 to July, 31st of 2020 for both desktop devices and mobile devices.

A weekly pattern is clearly identified, for both desktop and mobile devices (you had been warned…). For desktop devices, we observe, for all categories, a decrease in the number of Wikipedia pageviews from Friday to Saturday or Sunday for the majority of countries.

We also notice that the number of pageviews for all the categories decreases during the summer holidays and, less evidently, during the Christmas-New Year period on desktops compared to the rest of the year, as people tend to be less on their computer during holidays (as they should be, the only exception being Japan). While it is less pronounced, the weekly pattern is nevertheless there when looking at the numbers.

For both interfaces, an increase of the number of pageviews for all categories is visible for some languages due to the restrictions imposed by the government because of the COVID-19 pandemic from around March 2020 in general, depending again on the considered language. The rise is very pronounced for Italy, Japan and Serbia. It is relevant to note that both Serbia and Italy, were lockdowned.

Note: In Italy, the lockdown and the mobility change point happened on the same day, explaining why only one vertical line is displayed when there are still 2 in the legend.

This intuition has been confirmed, for most of the countries, in a more formal way through the use of the autocorrelation function to identify patterns. When studying the entirety of 2019, except for South Korea on desktops, we get peaks at lags k = 7 x n, meaning that we see a repetitive pattern every week. Thus, for the rest of our analysis, we decide to discard South Korea and to keep all the other countries.

2.2 Are work-week and week-end a real thing?

As we now know that a week pattern exists, we would like to see if some days of the week can be grouped together and if we can distinguish, through the way Wikipedia is consulted, some days that are similar within the week. Our intuition was that work-week days and week-ends would form two separate groups. It has been partially confirmed by a first approach which consists in computing t-tests between each day of the week in 2019 and looking at the p-value result.

The heatmaps above, by country and device, illustrate the results of the p-value obtained from t-tests between each day of the week of 2019.

Dark green cells means that we do not reject the null hypothesis of equal population means between the two different days (p-value superior or equal to 0.05)[3].

Please, note that the p-value does not reflect any notion of similarity between days and that we can’t really get more out of these results.

For most countries, no conclusions are evident from the results for mobile devices. From now on, we decide to discard mobile devices and only consider desktop devices. The idea of discarding mobile devices had always been on our minds as the paper A Large-Scale Characterization of How Readers Browse Wikipedia [4] states that Wikipedia sessions from mobile devices increase in the evening suggesting that mobile searches are correspond to activities that belong to all days of the week and that are thus not specific to subgroups of days of the week.

Thus, to go beyond this and to get a notion of similarity between days of the week, we make use of attention vectors as well as the wonderful and illustrative tools: similarity matrices and hierarchical clustering.

Attention vectors are a concept introduced in the study Sudden Attention Shifts on Wikipedia During the COVID-19 Crisis [1], which represent the daily distribution of topics with one entry per topic and entries summing to one. There are as many attention vectors as days considered in the study and each attention vector has 64 entries.

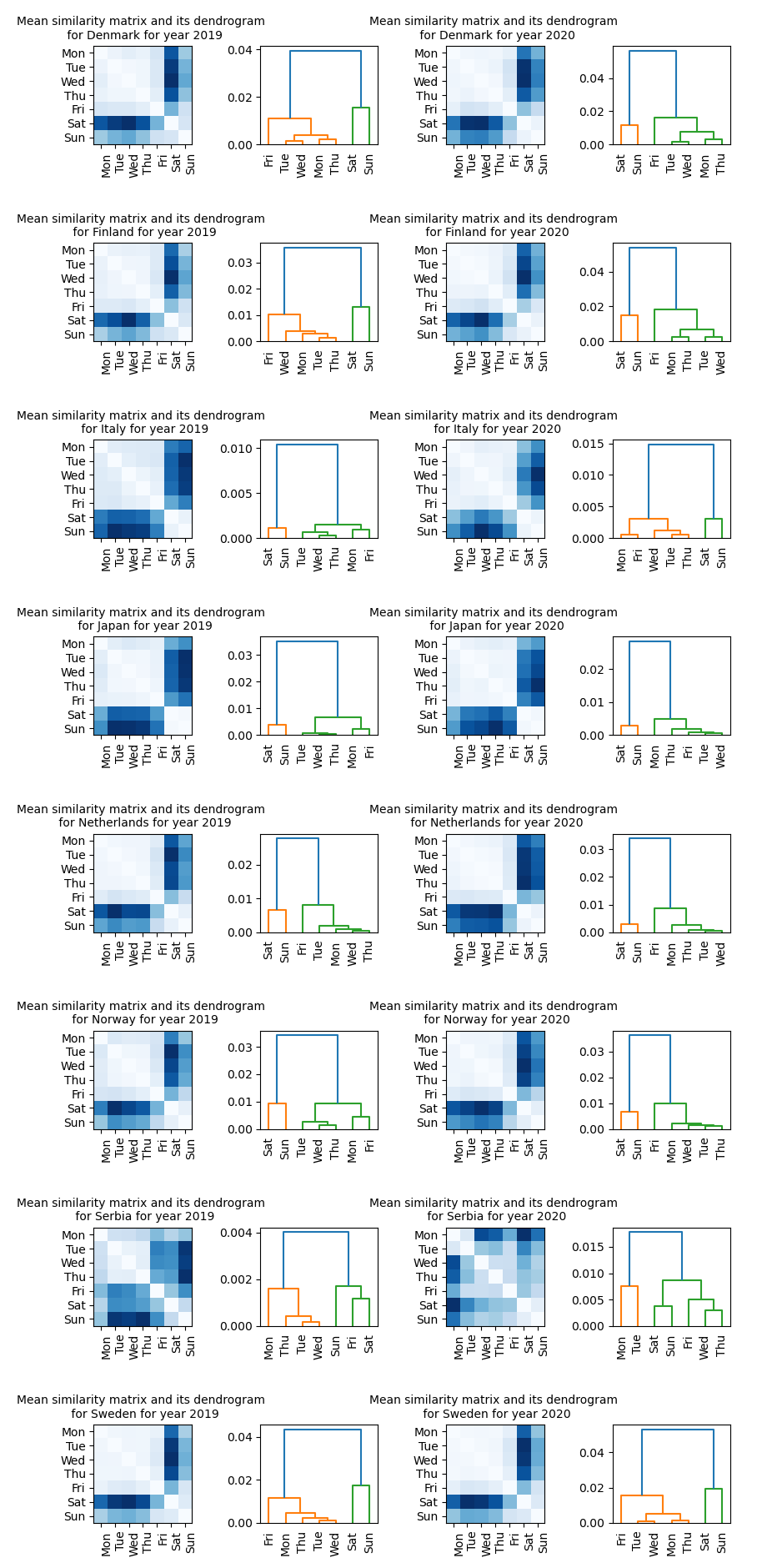

What we wish to do is compare attention vectors from different days of the week and find how close or distant they are. We create 28-day periods so as to have, for each year and each period, seven aggregation of attention vectors corresponding to each day of the week (these aggregations are the sum of the four original attention vectors of the same day contained in the period considered). The next step is to compare inside each period of each year, the seven attention vectors. We use the cosine similarity and summarize the results in a similarity matrix. The figure below shows the mean similarity matrix over all the periods in 2019 for each country studied.

The wonderful thing about the similarity matrix is that it is quite illustrative and easy to read. The results come as no surprise and are quite comforting. The darker the blue, the more distant the days of the week are based on their respective attention vectors. We see a pattern that is general for all countries: the top-right squares are darker in color and create a rectangle that separates two lighter colored triangles. These triangles are the groups of similar days that we’ve been looking for.

But given that we are engineers, we obviously have a solution to automatically find these groups. To be more precise than our eyes can see, we use hierarchical clustering to find the two most distinctive groups. Remember that our goal here is to determine what the identified weekly pattern looks like. A strong pattern is found if the intra-cluster distances are small while the inter-cluster distances are large. And again, we are not let down: these fancy dendograms show that the typical week of all countries (except Serbia, sorry) has two distinct groups: one containing all the days of the workweek and the other corresponding to the weekend.

So, let’s summarise things here. If you were wondering if Wikipedia consultations could reveal a certain pattern: the answer is yes. For almost all countries considered, Wikipedia consultations reveal two distinct groups within 7-day time frames and these groups turn out to be the work-week and the weekend.

3. Have we seen a change in the patterns of the week?

Now the ultimate goal of this study is to see how this pattern evolved when the COVID-19 pandemic kept everyone home. Without looking at the figure, what’s your guess? Are people working from home reaaally working? Maybe you suddenly wanted to bake cookies or watch just one more episode of Friends after that boring zoom call that made you already tired of working on a Tuesday morning? Our hypothesis is that these two identified groups became less distinctive (or in more technical terms, that the mobility restrictions resulted in a decrease in the inter-cluster distances). One easy way to find out is to reproduce the steps above for the data we have for 2020. The results are stunning. The similarity matrices are almost identical to the ones of 2019. What’s more, the hierarchical clustering outputs the same groups as previously identified (except for Serbia, sorry again).

It is not sufficient to simply find that there are two distinctive groups, we want to uncover why we find these differences. The figure below is there to tell you just that. It highlights the main topics, above a certain threshold, responsible for the difference in Wikipedia consultations between work-week and week-end for all the considered countries in 2019 and 2020. This means that the points in green represent topics with more views on week-ends than on weekdays and vice versa for red points. A previous study by Picardi et al. (2022) [4] found that STEM topics had more associations with working hours whereas topics linked with entertainment were characteristic of evening and night sessions. We could potentially expand on this as weekend activities are perhaps more related to evening rather than working hour activities during the work week.

Nothing surprising for the topics that make a difference, but isn’t the seemingly little to no change between 2019 and 2020 unexpected?

While the similarity matrices for 2020 suggested that the pattern persists even when mobility is restricted, it is not statistical evidence that a data scientist can be satisfied with. It is important to go one step further so we pull out our data science bag of tricks and make use of a quasi-experimental technique called difference in differences.

With this approach, we expect to observe and quantify the influence of mobility restrictions on the difference of the distribution of topic views of weekends versus workweeks, dissociating simultaneous changes (ex: seasonality effect) that would have happened even without the treatment. Our study is a natural experiment. Indeed, the COVID-19 pandemic happened due to factors outside of our control and the two groups were assigned randomly. This allows us to draw causal conclusions on the impact of mobility restrictions on the difference of Wikipedia’s topic consultation between weekends vs workweek.

We set two independent binary variables as : year (2019 or 2020), after_change (before or after mobility changepoint). We model y as a linear combination of those terms and the periods.

Our regressor y = B0 + B1 * period + B2 * year + B3 * after_change + B4 * after_change * year

The results are summarized in the table below.

| Country | Danemark da |

Finland fi |

Italy it |

Japan ja |

Netherlands nl |

Norway no |

Sweden sv |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| year:after_change coeff | 0.002466 | 0.009672 | 0.000469 | -0.002221 | 0.002427 | -0.000922 | 0.000526 |

| year:after_change pvalue | 0.323081 | 0.009905 | 0.603516 | 0.359529 | 0.447895 | 0.749307 | 0.834459 |

Now what does this all mean?

We are interested in the coefficient of interaction between period and year (B4) because it captures the multiplicative factor by which the distance between the mean week-end attention vector and the mean workweek attention vector increases or decreases as mobility is restricted.

The p-value associated to the coefficient B4 is larger than 0.05 for most countries meaning that the difference induced by mobility restrictions is statistically insignificant. In other words we conclude that mobility restrictions did not change the pre-existing topic consultation difference between work week and weekend. This is the case for Denmark, Italy, Japan, Netherlands, Norway and Sweden. You might complain about all this fuss just to show something that was evident from the similarity matrices, but it is important to be methodical! What’s more, we actually find a p-value that is lower than 0.05 for Finland. It means that mobility restrictions have changed Wikipedia’s topic consultation difference between week-end and work-week in a statistically significant sense. The value of the coefficient B4 (0.009672) indicates that there is an increase in difference of around 0.97%.

Again, it is interesting to explore at the topic level, what were the sources of changes for one particular group (work week or weekend) between 2019 and 2020.

It is interesting to see a few things:

- the topics Culture.Sport and Geography.Regions.Europe.Europe* are responsible for a negative change in the mean distance both for the consultation difference for weekdays between 2019 and 2020 and for weekends between 2019 and 2020.

- Indeed, during COVID-19 period, all sports competitions in all disciplines were canceled. The world of sports was shut down, so people had less reason to research it anymore.

- Regarding Europe, as the majority of the countries we study are European or near to Europe (except Japan), their citizens tend to look for information about their own country or their neighboring countries to educate themselves or by desire to travel, in normal circumstances. Because of the mobility restrictions imposed by each country, people were not able to travel. Thus, the consultation of pages related to this topic has decreased. Moreover, we can see that in Japan, there was a decrease in both Geography.Regions.Asia.EastAsia and Geography.Regions.Asia.Asia which further confirms this intuition.

However other topics were more solicited than usual. It is the case, for example of Culture.Media.Media* (in particular during the week-end) and STEM.Biology (in particular during the work-week).

- Due to mobility restrictions during Covid period, people spent more time at home and thus saw more movies, series or documentaries on TV. They had the time to make more research about these topics and to be more entertained than usual which can explain the positive change in the mean distance of the Culture.Media.Media* topic especially on the week-end without work.

- Because of this epidemic that has become worldwide, the news and information in general were constantly talking about Covid-19, the search for a vaccine, the pressure on hospitals and caregivers and in general about the medical and health fields. Thus, people tended to make more research about pages related to STEM.Biology topic for information and also for reassurance.

4. Conclusion

Finally, what can we conclude from all this?

What we thought:

- A weekly pattern of the Wikipedia pageviews exists.

- The Wikipedia pageviews depend on the day of the week and are different on work-week days and week-end days.

- The Wikipedia pageviews on work-week and week-end have changed because of the Covid period in 2020.

What we found:

- A weekly pattern in Wikipedia pageviews.

- Two groups of days based on the Wikipedia pageviews, work-week (Monday to Friday) and week-end (Saturday to Sunday).

- No statistically significant evolution of the difference between the workweek group and the week-end group going due to COVID-19 for most countries (except Finland)

- The difference between work-week and the week-end are defined by the same topics before and during Covid period.

- Despite no significant difference between the two groups, the proportion of some topics varied a lot from 2019 to 2020 impacted by COVID-19.

While our study shows that COVID-19 had no significant impact on how Wikipedia pages were viewed on week-ends and week-days before and during the COVID-19 period, it seems difficult to translate this absence of impact to our general habits. Wikipedia data can only partly describe habits of people. While it does give some insights on the behavior of people when mobility restrictions were in place, it comes short of giving a full perspective of people’s daily and weekly habits. Additional data such as search engine logs would perhaps allow for such an analysis.

As we often hear, a picture is worth a thousand words so we’ll leave you with this one:

5. References

[3] Steven Goodman, “A Dirty Dozen: Twelve P-Value Misconceptions”, 2008